Anatomy

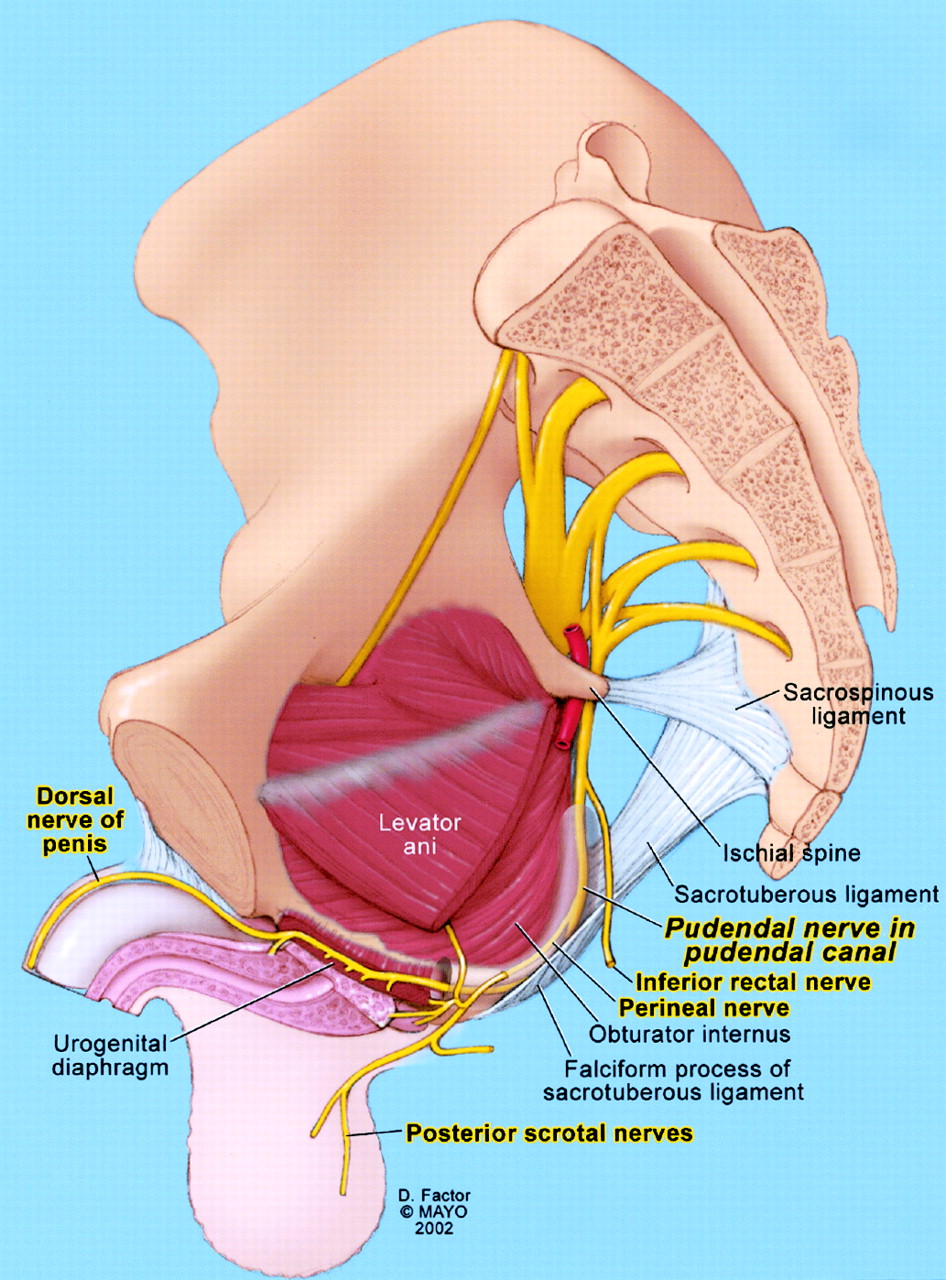

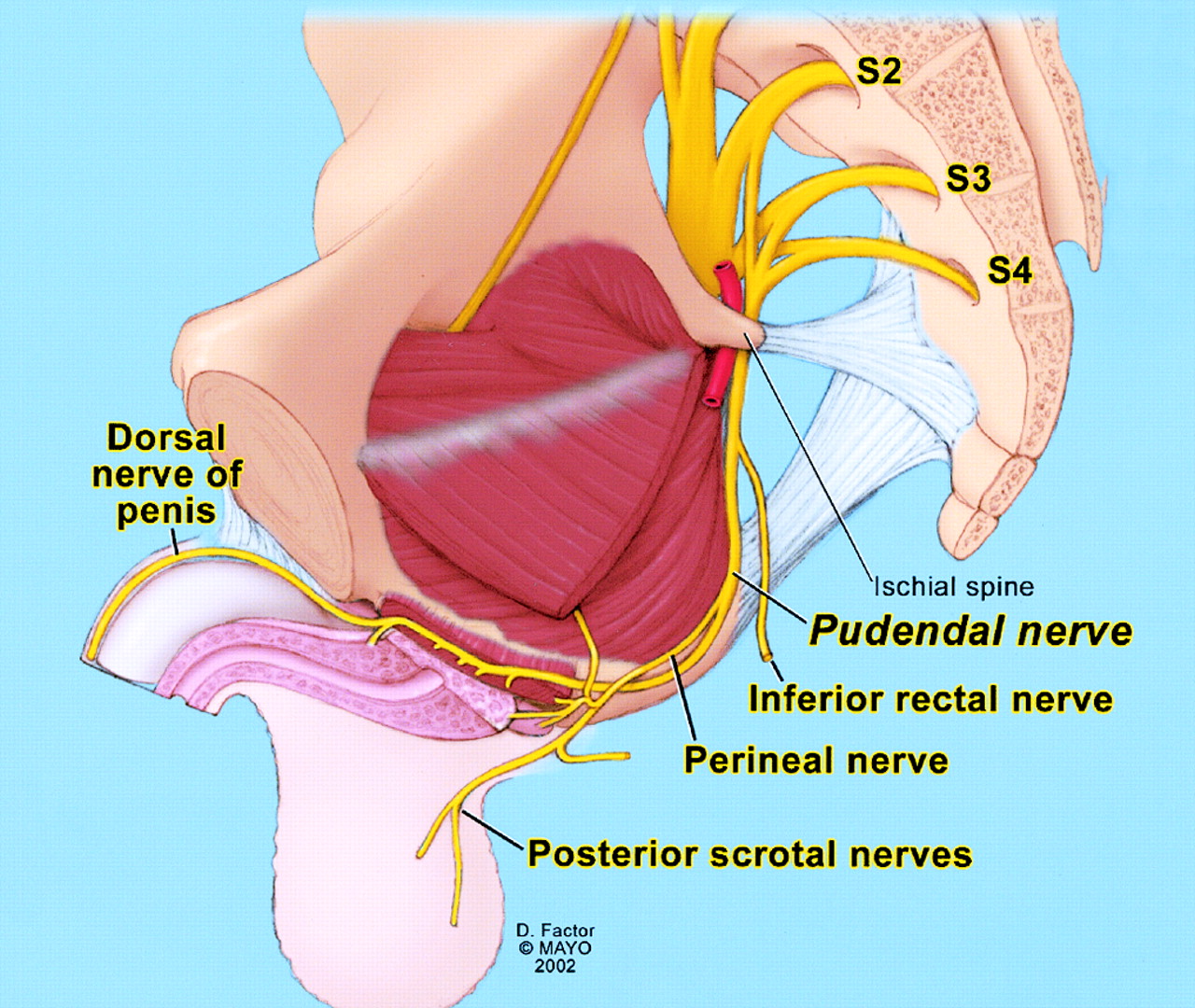

The pudendal nerve is a sensory, autonomic, and motor nerve that carries signals to and from the genitals, anal area, and urethra. There are slight differences in the nerve branches for each person but typically there are three branches of the nerve on each side of the body; a rectal branch, a perineal branch and a clitoral/penile branch.

LEGEND

This is a sagittal view of the pelvis. Pretend you are in the middle of the pelvis looking sideways. The pudendal nerve comes down from sacral nerve roots 2,3, and 4, runs underneath the piriformis muscle, goes between the (SS)sacrospinous and (ST)sacrotuberous ligaments at the ischial spine, travels through alcock’s canal between the obturator internus and levator ani muscles, and divides into 3 branches. There are variations in where the branches come off in each person. In reality, there is a small space between the SS and ST ligaments. This is not shown in the picture, but according to pudendal nerve entrapment surgeons, this space can be very tight.

(Source – Anatomy: A Regional Atlas of the Human Body, 4th Edition, by Carmine Clemente, 1997)

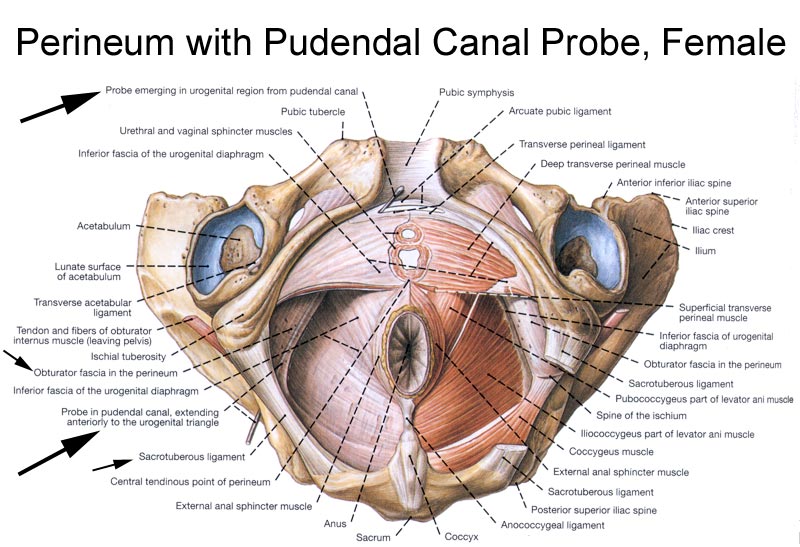

Two thirds of PN sufferers are women, according to Dr. Robert’s statistics. This image shows the entire region served by the female pudendal nerve in extreme detail. To study it, find the pudendal nerve and follow it. Note how it is perfectly symmetrical, with left and right sides. Observe the many fine branches, not all of which can be shown on the drawing.

(Source – Anatomy: A Regional Atlas of the Human Body, 4th Edition, by Carmine Clemente, 1997)

These are the images to print out and show your doctor, and are sized to print well on a sheet of paper. Use Normal or Best mode (not Draft), and print in color if you can. Mark where your pain is and discuss what could be causing it. With the right doctor and good preparation on your part, you can move swiftly through the diagnosis step.

Comparison of Pudendal Nerve Drawings

Comparison of Pudendal Nerve Drawings

This compares images prepared by Doctors Robert and Beco. Placing them side by side and identifying the key items allows you to more easily grasp the route of the pudendal nerve, along with the potential entrapment locations on the route. The most common point of entrapment is at the ischial spine, where the pudendal nerve runs under the sacrospinal ligament. The second most common is in the pudendal canal. These are the two principle entrapments that Dr. Robert’s surgical protocol resolves.

Submitted by Kevin Harwood. As he describes it: “Be certain that you see the last attachment, as it is an ‘autographed,’ Netter image personally-manipulated by Professor Robert. He manipulated this image to demonstrate the pudendal nerve exactly as he finds it in situ. I am not sure if this is an artist’s proof edition, signed and numbered, or just a regular lithograph, but Professor Robert did give it to me.”

The pelvic region and route of the pudendal nerve are so three dimensional they are hard to visualize. This image does an excellent job of showing bone structure, nerve paths, and ligaments in a 3D manner. Note especially Alcock’s Canal and where the pudendal nervepasses under the sacrospinal ligament where it attaches to the ischial spine. These two locations are where most pudendal nerve entrapment occurs, and is what Prof Robert’s surgical procedure alters to “free up” and “decompress” the nerve.

(Source – Anatomy: A Regional Atlas of the Human Body, 4th Edition, by Carmine Clemente, 1997)

To the non-medical person (the layman), the pelvic area is hard to understand due to its 3D nature and complexity. This image starts you off on understanding this region by showing the key items: the pelvic bone, the ischial spine, and the ischial tuberosity. Note where the fold of the buttocks is in relation to the ischial tuberosity. When you sit, the two ischial tuberosity bones take about 75% of your body weight. These bones are frequently called the “ischials” or “sitting bones.” The coccyx can also be seen.

(Source – Anatomy: A Regional Atlas of the Human Body, 4th Edition, by Carmine Clemente, 1997)

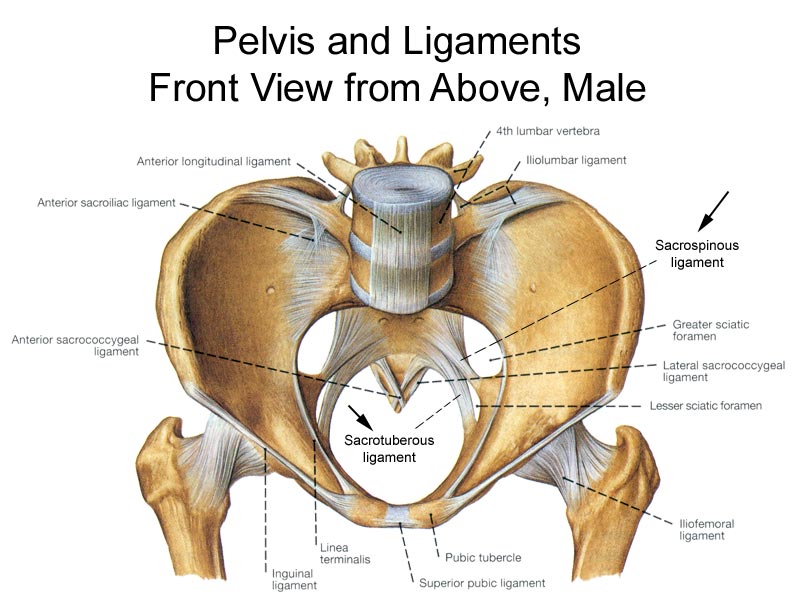

The above image of the pelvis was just bones and the body was drawn in, so you could see where the pelvis is. This image takes the next step. The body is removed. Ligaments are added. The features of interest are the sacrotuberousand sacrospinous ligaments. These are the two ligaments that Dr. Robert’s surgical procedure modifies to free the pudendal nerve. As his article says on pages 7 and 8:

“The surgical principle is simple: the gluteal incision is made in the axis of the fibers of the gluteus maximus m. on either side, with a transverse limb passing over the coccyx and thus situated at the level of the ischial spine. The posterior aspect of the sacrotuberal ligament is stripped free of its muscular attachments. The sacrotuberal ligament is windowed over 2-3 cm (Fig. 10).“The pudendal neurovascular bundle is then seen crossing behind thesacrospinal ligament. The latter is divided and the nerve can then be transposed in front of the spine, thus gaining precious centimeters thanks to this freeing (Fig. 11). The sacrifice of these two ligaments is not accompanied by any bio mechanical disorder.”

(Source – Anatomy: A Regional Atlas of the Human Body, 4th Edition, by Carmine Clemente, 1997)

Next we walk around to the other side for the front view of the pelvis. This is radically different. Since we can no longer see where we sit down, the features of interest are mostly hidden from view. The two ischial tuberosities can still be seen. They make great reference points. The tip of the coccyx can just barely be seen. The important concept in this image is the way the pelvis holds up the internal organs in the abdominal cavity, much like a bowl holds jello. The next image will take a look into that bowl.

(Source – Anatomy: A Regional Atlas of the Human Body, 4th Edition, by Carmine Clemente, 1997)

Pretend you have poked your head inside your stomach and are looking down. This is what you would see, if everything except pelvic bones and ligaments were removed. Notice the two key ligaments again. Imagine all your organ weight pushing down as you go about your everyday vertical existence. Now, imagine adding to that pressure by sitting long amounts every day. This pushes from the bottom, right on everything that’s down there. Pushing forces are magnified wherever there is a bone protruding into the pelvic cavity. Guess which one takes the cake here? Why, it’s our old friend, the ischial spine, once again. Prof Robert describes the problem that this bony protrusion causes in his article: the pudendal nerve” describes a curve which drags it around the region of the ischial spine, which it straddles like a violin string on its bridge.” A similar problem occurs in Alcock’s canal. For those who are susceptible, the result of all this pressure and nerve vulnerability is PN or PNE.

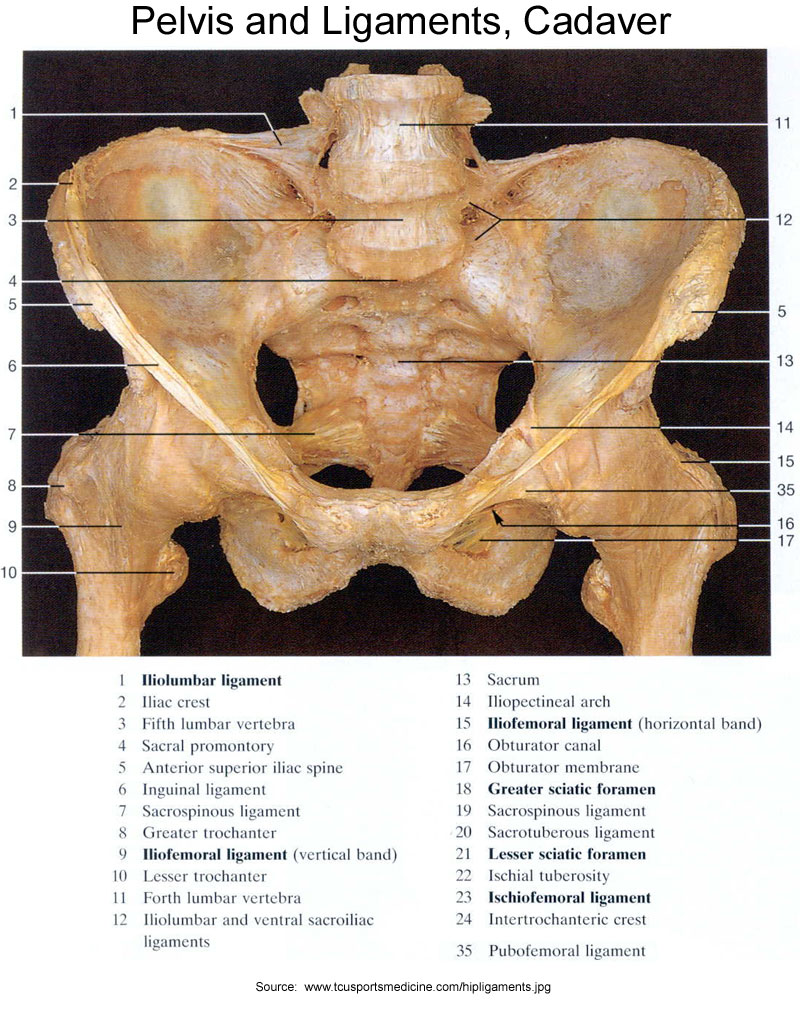

This is a little gruesome, but the detail is there. Note the roughness on the ischial tuberosities and the very bowl like shape. When you stop and think about what you’re looking it, what it does, and how well it does it, it’s really an engineering marvel.

You may be wondering, “Why all these views of bones and ligaments? Isn’t this a nerve problem?” This is true, it is a nerve problem. But to best self-manage our case, we need to have an accurate, complete model to understand why the nerve becomes inflamed or damaged. The nerve doesn’t damage itself: something else has to do that. That something else, for PNE, is bones or ligaments pushing for a long time at a pressure level far above what our poor little bodies were designed for. Muscle, fat, and other soft tissue doesn’t cause concentrated pressure: only harder things can do that. As you probably know, Homo sapiens was not designed for sitting. Our body evolved to mostly hunt and gather, and to sit only a little. Modern civilization has reversed this: we sit a lot and walk or stand very little. The inevitable result? A design mismatch and PNE. Some doctors have remarked it’s a wonder that many more people don’t have PNE.

(Source – Anatomy: A Regional Atlas of the Human Body, 4th Edition, by Carmine Clemente, 1997)

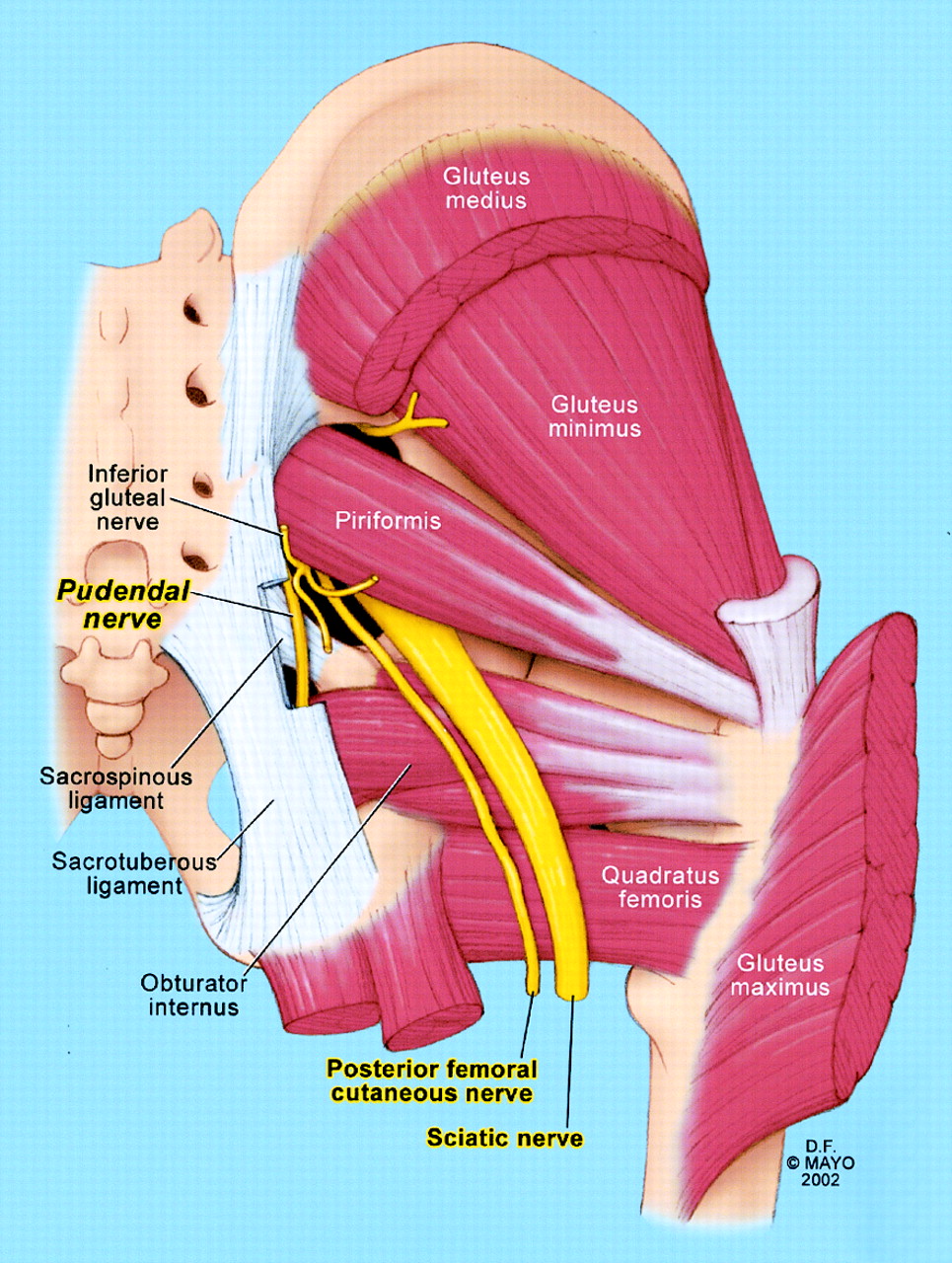

Now we get really bold. Imagine you have just followed Alice in Wonderland into her magical, miniature world and are now two inches tall. You are standing in the bottom of the pelvic cavity. Your view has been improved by splitting the spine temporarily. (After all, we wouldn’t want to hurt anyone.  You look over towards the right hip. This is what you would see. All our old friends are there: the sacrospinal andsacrotuberous ligaments, the ischial tuberosity, and the by now infamous ischial spine.

You look over towards the right hip. This is what you would see. All our old friends are there: the sacrospinal andsacrotuberous ligaments, the ischial tuberosity, and the by now infamous ischial spine.

You look over towards the right hip. This is what you would see. All our old friends are there: the sacrospinal andsacrotuberous ligaments, the ischial tuberosity, and the by now infamous ischial spine.

You look over towards the right hip. This is what you would see. All our old friends are there: the sacrospinal andsacrotuberous ligaments, the ischial tuberosity, and the by now infamous ischial spine.(Source – Anatomy: A Regional Atlas of the Human Body, 4th Edition, by Carmine Clemente, 1997)

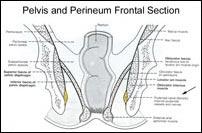

You are still two inches high. Now put on your best X-ray glasses. Imagine a patient is lying down, perhaps after a pleasant picnic on the Rhine. You step between their legs and look towards the bottom of the pelvic region. You see a perfect cross section, exposing all those little things running up and down at the point of cross section. Be sure to notice where our best friend, the pudendal nerve, runs. The poor stressed out fellow has not yet reached the ischial spine, which it does only about two inches further down. Note also the nerves running under the ischial tuberosity. These nerves are heavily padded by the gluteus maximus muscle and fatty tissue, but are still highly vulnerable to damage, because they have rock hard bone behind them.

Now, imagine the patient you are viewing gets up and sits down in a chair. Can you see how the chair pushes on the all that tissue, which in turn mashes those nerves against the bones or ligaments they run over? On, I pity the nerve that lives such a down trodden life! Next, imagine sitting on a bicycle. The bicycle seat gets right up in there and pushes ever so hard on the pudendal nerve, who frequently is totally overwhelmed by the experience and has been known to go on strike! Or so all these little nerves have been telling me…

Thank you for joining us on our tour of the pelvic region. If you have any further questions, just ask our intrepid guides, who can be found in the group discussion areas. The next tour will start in approximately 30 minutes…

The pudendal canal, also called Alcock’s Canal, is the second most common location of pudendal nerve entrapment, after the ischial spine. During Dr. Robert’s surgical procedure, if necessary the pudendal nerve is “freed up” from the pudendal canal by very carefully cutting the obturator fascia (sheathing) that lies over the canal, and gently working the nerve out. This is a rather delicate surgical technique. Do not try this at home!

(Source – Anatomy: A Regional Atlas of the Human Body, 4th Edition, by Carmine Clemente, 1997)

This image is taken from the one below and enlarged so you can see enough detail. Note thebundle of pudendal nerves, veins, and arteries running together through the pudendal canal. This image also gives amazing detail on all those tiny yellow nerves in the anal and perineum regions. This is top notch artistry.

(Source – Anatomy: A Regional Atlas of the Human Body, 4th Edition, by Carmine Clemente, 1997)

This shows different detail from the Male Pudendal Nerve image in Key Images. Superficial dissection allows showing many more nerves, as well as the pudendal canal.

(Source – Anatomy: A Regional Atlas of the Human Body, 4th Edition, by Carmine Clemente, 1997)

This shows the pudendal canal as it travels along the lower obturator internus muscle and pelvic bone. The canal has been highlighted in yellow. Note the potential for intense compression of the canal by bicycle riding. Many new bicycle seat designs have a depression in the center to reduce perineum pressure. However, this only increases pressure elsewhere, resulting in an even higher chance of injury. Please don’t be fooled by such fancy seat designs.

(Source – Anatomy: A Regional Atlas of the Human Body, 4th Edition, by Carmine Clemente, 1997)

The route of the pudendal canal is so hard to show in illustrations that this image takes an ingenious approach. A thin steel probe has been inserted to show where the canal runs. Note how deep into the patient a doctor would have to go to free up the pudendal nerve in the canal. This, of course, is why this surgery is so demanding.

This shows detail from the above image. No thumbnail shown since detail from above image.

Schematic anatomy of deep dissection of gluteal region. Most of gluteus maximus and medius muscles have been removed. Segment of sacrotuberous ligament also has been removed, revealing pudendal nerve. Pudendal nerve emerges from pelvis inferior relative to piriformis muscle and enters gluteal region medial relative to sciatic nerve, superficial relative to sacrospinous ligament, and deep relative to sacrotuberous ligament. After coursing around sacrospinous ligament, pudendal nerve reenters the pelvis. (source)

Schematic anatomy of pudendal nerve. Drawing illustrates pudendal nerve arising from sacral nerve roots S2–S4, exiting pelvis to enter gluteal region through lower part of greater sciatic foramen and reentering pelvis through lesser sciatic foramen. Pudendal nerve gives rise to inferior rectal nerve, perineal nerve, and dorsal nerve of penis or clitoris. (source)

Drawing shows pudendal nerve in pudendal (Alcock’s) canal. Inferior rectal nerve arises from pudendal nerve before entering canal. Note location of falciform process of sacrotuberous ligament, which is possible site for pudendal nerve entrapment. (source)

(Source – Anatomy: A Regional Atlas of the Human Body, 4th Edition, by Carmine Clemente, 1997)

This shows the various pelvic nerves as they leave the lower spine. The pudendal plexus is where the pudendal nerve orginates. Plexus means “a structure in the form of a network, especially of nerves, blood vessels, or lymphatics.” From the pudendal plexus, the pudendal nerve travels down to the anal, perinum, and genitalia. This image does a good job of showing how, in the seated position, the pudendal nerve receives so much pressure.

This well drawn sketch is from Dr. Antolak, formerly of the Mayo Clinic. Note how the nerve travels under the sacrospinous ligament near the ischial spine and then branches out. This is a great job of showing the three dimensional route of the nerve. Note the three branches of the pudendal nerve and how they serve different areas. Many male sufferers have severe pain in these areas. If you are unfortunate enough to be one of them, this image allows you to almost feel where the offending nerve is. Hopefully that will help you better discuss your case with your doctor.

(Source: Volume 1, Nervous System, by Frank H, Netter, M,D., 1968.)

This shows the route the pelvic and pudendal nerves take as they feed off of the sacral plexus. Click on the link above, then click on the pop-up to enlarge the picture. The text explains much futher detail.

The male version of the above. No thumbnail shown. Click on the link above, then click on the pop-up to enlarge the picture. The text explains much futher detail.

This is an incredibly cool web site, where you can dissect and resect the female pelvis. It gives you a three dimensional look of what the pelvis looks like, the particular muscle groups within the pelvis and where some of the larger nerves are within the pelvis, including the pudendal nerve. This is a great place to start your journey in identifying major structures within the pelvic region. When you get to the site, scroll up or down on the right or click an item on the right. Have fun!

Pudendal Nerve by Dr. Robert

Pudendal Nerve by Dr. Robert

Pelvis and Ligaments, Rear View

Pelvis and Ligaments, Rear View

Pelvis and Ligaments, Cadaver, Front View

Pelvis and Ligaments, Cadaver, Front View Pelvis and Ligaments, Vertical Cross Section

Pelvis and Ligaments, Vertical Cross Section Pelvis Cross Section, Horizontal

Pelvis Cross Section, Horizontal

Male Perineum, Superficial Dissection

Male Perineum, Superficial Dissection

Perineum with Pudendal Canal Probe

Perineum with Pudendal Canal Probe Deep Dissection of the Gluteal Region

Deep Dissection of the Gluteal Region Schematic Anatomy of the Pudendal Nerve

Schematic Anatomy of the Pudendal Nerve